Organoleptic Identification Techniques in Herbal Medicine Manufacturing

When it comes to creating herbal medicine, quality control is everything. Especially if you’re trying to produce standardized extracts from raw plant material. Anyone who has ever worked in herbal manufacturing knows how tricky consistency can be. Over the years, working for different companies and helping build out their QC protocols, I’ve learned that one of the hardest parts of the entire process is simply coming up with ways to ensure consistent results.

And honestly? It all begins with the raw material. Before any extraction, any batching, any fancy equipment — the plant matter itself has to be examined, evaluated, and sometimes rejected if it doesn’t meet internal specifications. One of the most reliable tools I use for every intake procedure is something called organoleptic identification. In short, it’s the practice of using your five senses to identify and assess the quality of herbal material.

This technique is just as useful in a large‑scale manufacturing setting as it is in your home apothecary. Whether you’re making a 50‑gallon tincture batch or a jar of tea for your family, your senses will tell you more than you think.

So let’s walk through each sense and how it supports proper herbal identification.

Eyesight: Observing Plant Structure and Color

Our eyes give us the first impression, and in herbal work, that first impression matters. Color and structure are two of the biggest indicators of quality.

Fresh plant material tends to hold onto its natural color. As herbs age, they oxidize: greens turn brown, bright petals dull out, roots lose their vibrancy. While some color change is normal, excessive browning usually means the material is old or improperly stored. And since fresh material typically contains the highest concentration of medicinal compounds, this is something you want to catch early.

Structure is equally important. Unfortunately, adulteration is a real issue in the herbal industry. Some herbs are commonly “cut” with cheaper plant matter to reduce cost. It’s shady, but it happens more often than people think. In order to avoid contaminants in your final product ensure that you are checking not just for the quality of incoming plant material but also its biological identity.

To protect your formulas:

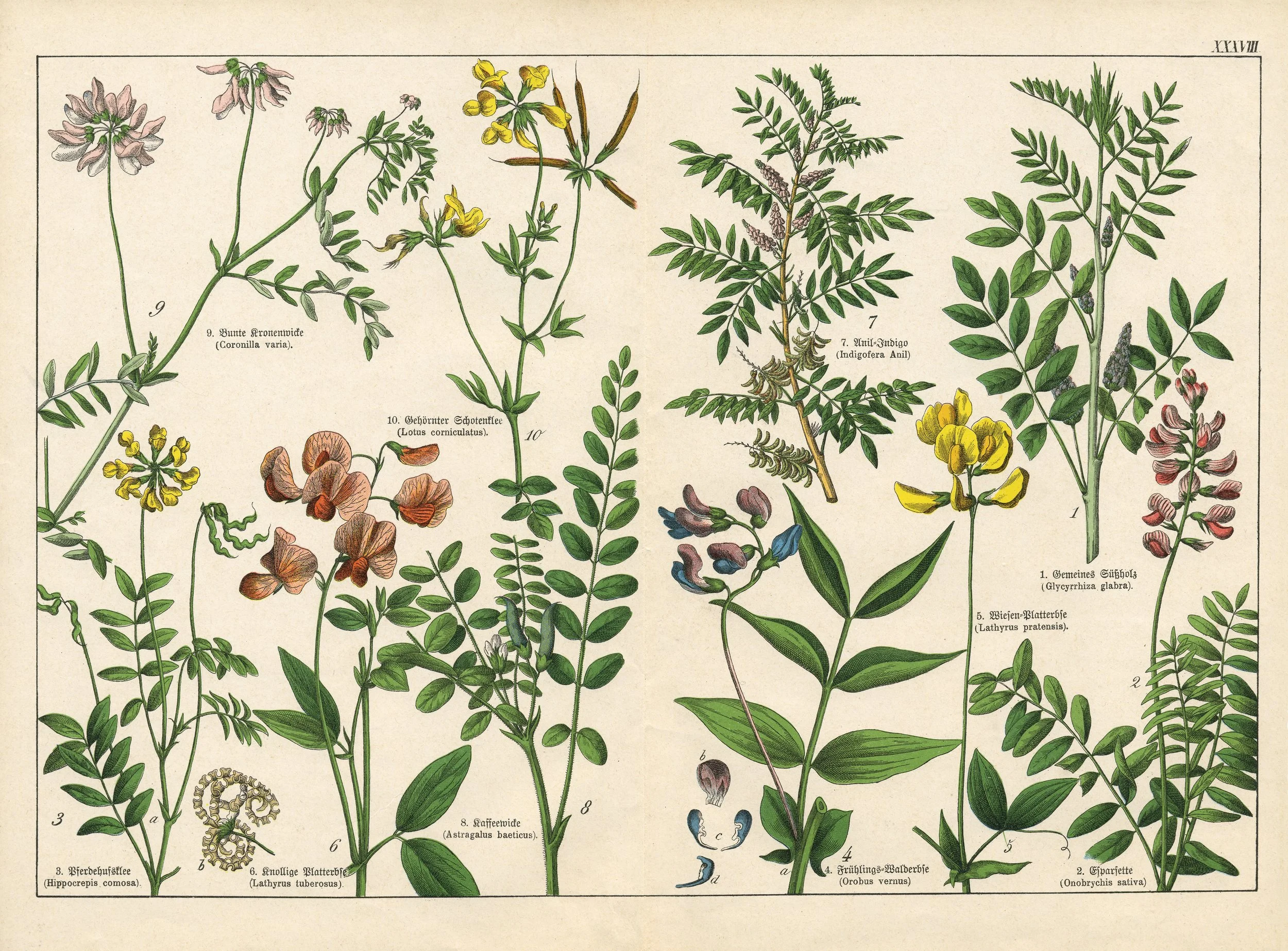

Keep a trusted botanical reference book nearby

Compare leaf shapes, venation, flowers, stems, and bark

Even in ground material, look for intact fragments that reveal identity

Sometimes the differences between species are subtle. When that happens, it’s time to lean on your other senses.

Scent and Taste: Adding Another Layer to your ID

The junction between scent and taste is especially prevalent when identifying plant species. Even though these are separate senses the overlap between the two is undeniable. Biologically they are both captured with your olfactory system, each one affecting the other.

Scent is usually the second sense you automatically engage. A plant should smell like itself. If something smells “off,” musty, sour, or just not right, that’s often your first clue that the material is spoiled or contaminated.

But this is often a nuanced observation, which is why I have grouped this sense with taste. Together they can indicate what one alone may struggle to do. In the herbal world, taste profiles help classify plants and often reflect their actions in the body.

Over time, you start to recognize patterns. Astringent herbs have a specific mouthfeel compared to ones that stimulate our mucosal membranes. Herbs high in mucilage tend to have a mouth coating effect which mimics their action in the body. These herbs tend to support a soothing of the gastrointestinal tract. On the other hand herbs with more of an astringent effect kind of make you pucker a bit. These may be stimulating to the liver or even act as bitters helping to stimulate rather than soothe digestion.

Astringent herbs create a puckering, drying sensation.

Bitter herbs stimulate digestion and liver activity.

Mucilaginous herbs coat the mouth and soothe tissues.

Sweet herbs (like licorice) contain glycosides that are unmistakable.

For example, burdock root is extremely bitter and astringent — and that taste mirrors its action in the body, stimulating bile production and supporting detox pathways. Licorice root, on the other hand, is naturally sweet due to its glucoside content, making it easy to identify even in blends.

Taste and scent together can confirm what your eyes suspect.

Texture: The Final Component to Organoletic ID

Touch is the last major sense we use in organoleptic identification, and it’s more important than people realize.

Properly dried herbs should feel crisp, firm, and lightweight. As plant material ages or becomes contaminated, it starts to soften. Microbial activity can make herbs feel slightly rehydrated or pliable — a clear sign that something is breaking down.

Texture also helps differentiate species with similar appearances. Some roots are naturally fibrous, some leaves naturally velvety, some barks naturally brittle. Over time, you build a tactile memory that becomes part of your identification toolkit.

Bringing It All Together

Organoleptic identification is one of the oldest herbal skills we have, and it remains one of the most reliable. Whether you’re working in a manufacturing facility or mixing herbs in your kitchen, your senses are powerful tools for ensuring quality, safety, and consistency.

And the more you use them, the sharper they become.